Seven principles of successful technology due diligence

The Theranos story is as avoidable as it is dramatic. The company claimed its desktop technology could rapidly perform multiple disease-detecting tests simultaneously from just a few drops of blood (while large vials of blood and lab testing would usually be needed). The possibility of addressing needle phobia, reducing healthcare costs, and increased convenience attracted hundreds of millions of US dollars of investment – only for it to be revealed that the technology didn’t work as promised and its failings had been covered up. The exposure of false claims begs the question: what happened to credible technology due diligence before making a significant financial commitment?

At CDP, we’ve been performing technology due diligence for decades, helping our clients assess target technologies for potential rights acquisition, or investing in the company that owns the technology. Our due diligence provides an independent view of how far away these target technologies and companies are from managing their risks, opportunities and milestones.

For technology due diligence to be successful, we apply seven principles, which I’ll share with you in this article. They could certainly have helped Theranos’ investors – but are useful for other, less dramatic acquisitions, too.

Take a wide view

Investment and acquisition risk of a technology can exist in many places, depending on if it’s in development or on the market.

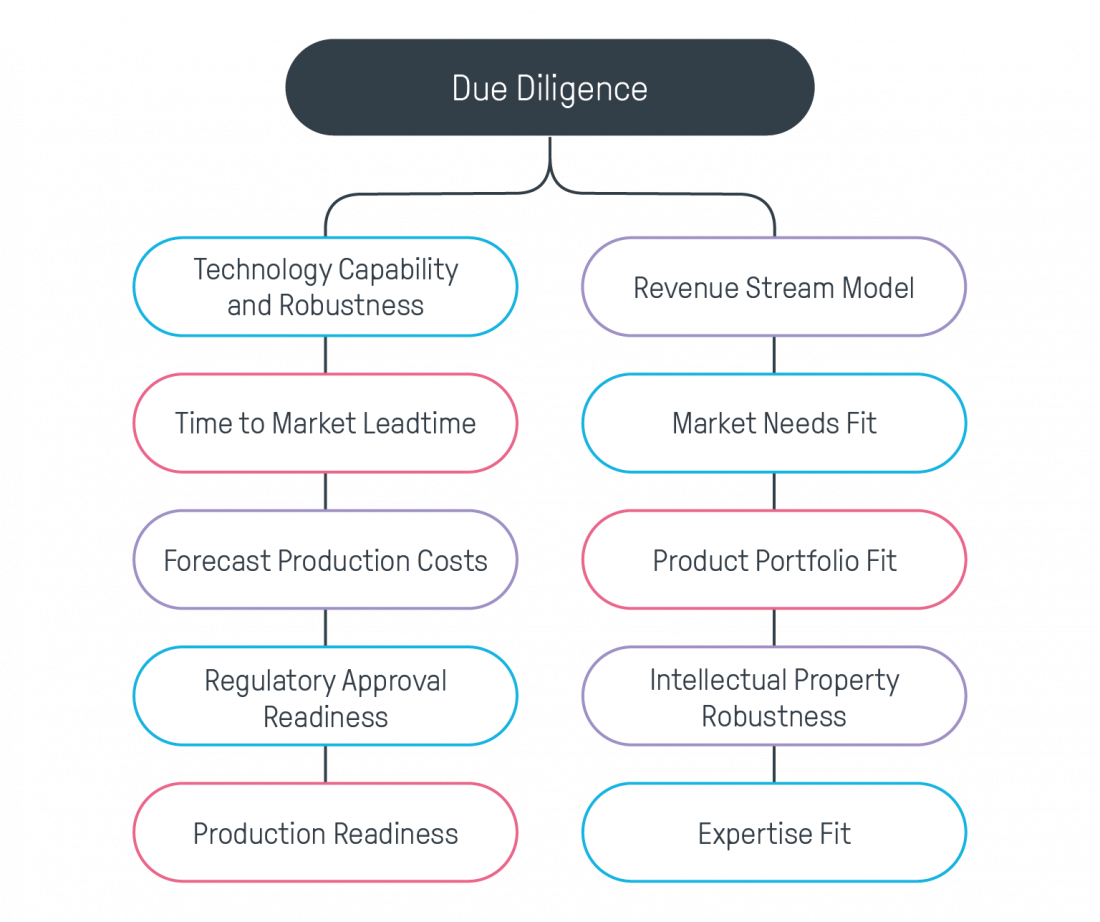

Figure 1: Potential assessment areas for technology due diligence

With time and effort for due diligence activities being limited, it’s understandable that choosing not to focus your investigation on areas that appear less risky might feel sensible. But we’ve found that success stories such as granted patents, regulatory approvals, great PR, and high sales figures don’t always lessen the risks in those areas.

The key to managing the risk perceptions and defining the correct plan for due diligence is seeking input from a multidisciplinary team, working collaboratively to explore the importance and probability of issues and strike the right compromises to fit the assessment work into the allotted time.

Although due diligence activities can flex as you go along depending on your findings, an initial plan should be in place that defines the areas and depths to explore.

Mind the skills gap

Building the right due diligence team means keeping clear of a couple of hazards.

The first is assuming that, because you might only lightly explore some areas, you just need generalists who can cover many bases. The problem with this approach is that sometimes the findings of your investigation compel you to go deeper, or your generalist may not even realize that you need to go deeper because of their limited expertise.

The solution is investing time in finding specialists for the different areas – either to give their input from the start or to be brought in as needed. Depending on the target technology, your team might consist of engineers (mechanical, electronic, software, human factors, manufacturing), scientists, market researchers, and IP attorneys – and, ideally, individuals who are experienced in the sector in question. For example, in the case of Theranos, a pathologist could have sense-checked the evidence for the claim you can run so many tests on a few drops of blood.

The second pitfall is cutting corners on the team make-up, either because you don’t have the expertise in-house, or the team doesn’t have the time to investigate the technology with the attention needed. The solution is to purposefully ringfence your in-house experts and consider bringing in external specialists who can add other perspectives. For example, one of our clients was considering making significant investments with several technology companies. With only in-house financial and market experts on hand, they took the step to commission our technologists and engineers to carry out comprehensive due diligence – resulting in more informed decisions on where (and where not) to invest, and great returns.

Figure 2: Potential technical experts required for technology due diligence

Engage to establish trust

With confidentiality agreements in place, it’s a plus when the company which owns the target technology is willing to open up its books for detailed scrutiny of its assets – it makes your work easier, shows they’re keen, displays trust, and is a sign of what your future relationship might be like.

Often, though, you might not get all the information you want – the answers don’t exist, work is unfinished, it’s messy, or enveloped in positive spin. It’s understandable that the target company might be nervous about being under the spotlight and needing to secure investment. To see through this, you need to create the conditions that increase trust to foster transparency. Often, trust is increased by establishing a personal connection with the target company. Meeting face-to-face, COVID-19 restrictions allowing, is one step, but a more effective approach is understanding the technical, organizational, and commercial challenges the company had when developing the technology, so your expectations are realistic, and your communication is empathetic.

Work around confidential information

Even given your best efforts to establish trust, target companies still might choose not to disclose everything, because unintended leakage of trade secrets can cause significant business harm.

How can you assess if you can’t see everything? What if the thing being hidden isn’t a trade secret but a fundamental flaw or gap in the offering?

This is where your subject matter experts come into play. They should be able to formulate investigative questions that don’t force secrets to be disclosed – such as asking about the precepts behind the technology, associated engineering principles, methods of test, or quality and regulatory requirements.

Black-box testing (testing a system without knowing how it works) is another approach which helps navigate confidentiality. In the case of Theranos, the potential investors could have asked for the machine to be tested in front of them with provided samples to see if the results were as expected. If a product is on the market, you can try to get hold of a sample of it for technical testing, market testing or tear-down (disassembly to study how it works and is made).

Remember other information sources

A client commissioned us to estimate the production costs for a product to figure out the potential profit and risk areas. This needed to be done without speaking with the company that owned the target technology to avoid alerting other suitors.

Starting out with just one photo given to us by our client, we researched publicly available information such as patents, scientific papers, conference presentations, and other marketing material to estimate the product’s construction, material type, material content, and manufacturing processes with reasonable accuracy. Similarly, we found critical risks that informed questions we went on to ask the company later.

Admittedly, public domain information can be dated and fragmented, but it’s a source worth considering. It might be able to fill in gaps when information finding is restricted, and potentially find other risks and opportunities you may want to ask the target company about.

Don’t ignore the fundamentals

We recently performed due diligence on a target product that had been approved by regulators, used by other companies, and created a stir with its solid intellectual property.

We were told the technology was sound but that there were challenges around manufacturing it in high volumes. Despite assurances from our client and the target company, we still chose to scrutinize the core technology, especially around a novel critical feature which the whole product hinged on.

Working against the clock, we discovered a fundamental flaw with that critical feature that no one had caught before, shocking our contacts at the target company. It threw their concept and the robustness of their intellectual property into question and found a risk that the product could cause serious harm.

The finding was so significant with such a low chance of resolution that our client stopped the potential acquisition process and the target company aimed to restrict the product’s use.

The lesson: ask yourself, “Imagine there was a potential problem in this one area; how impactful would that be compared to another failing in another area?” This line of thinking should prioritize your efforts. Usually, the area where the cost of modification is highest is the technology’s fundamentals.

Be balanced

Looking back to the example above, you might think finding an investment-stopping flaw in the technology that no one else had caught is a sign of good due diligence. It is – but good due diligence isn’t about seeing how many negatives you can collect.

Good due diligence is about a solid process and approach – knowing you were thorough, applied the right experts, were equally motivated to find the positives and negatives, and sized the risks and opportunities with impartiality – leaving the decision to invest to the client, based on their appetite for risk.

In other words, it’s just as important that due diligence enables you to identify fantastic technology for potential acquisition as it is that it helps you avoid making a bad investment.